01: The Many Hats of the Occ Doc

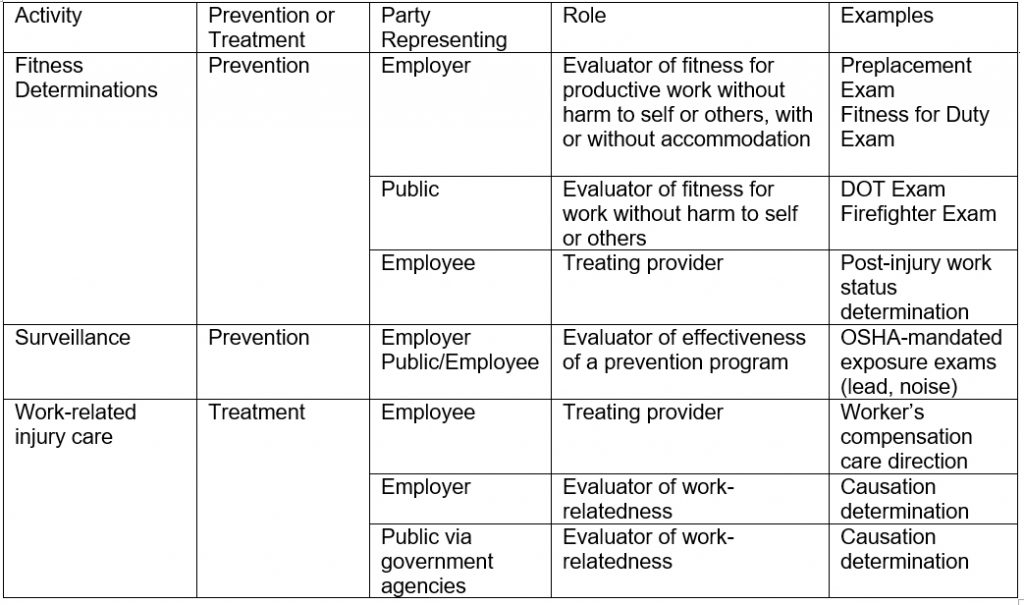

, DO, MPH, MHPE, FACOEMOccupational physicians wear many hats. Somewhat unlike the traditional practitioner, who is focused solely on caring for, or directing care for, the individual patient, the “occ doc” is frequently required to represent many points of view. Some practitioners are uncomfortable with this role—which requires some explanation. It may be helpful to categorize much of the work of the occ doc into three primary activities: fitness determinations, surveillance, and work-related injury care, as well as whom he or she represents with each activity. The following chart provides a good foundation for understanding the basics of occupational medicine but is not meant to be an all-inclusive list of possible functions or benefits of each activity.

Often, when I’m asked what I do, I say that I answer these three questions:

- Are the work and the worker a good match? (Fitness determinations)

- Is the work or work environment injuring the worker? (Surveillance)

- How do I best manage an injured worker’s injury? (Work-related injury care and causation analysis)

Fitness Determinations

Occupational medicine providers frequently evaluate worker fitness—addressing whether the worker and the work environment match. In doing so, they help determine the worker’s level of injury risk to him or herself or to the public (including coworkers) in light of any preexisting conditions. This function can be performed in a preventive or informational visit—a preplacement, fitness for duty, accommodation, or disability evaluation exam—or during a treatment visit. Providers should consider every treatment visit another fitness for duty evaluation. And each visit should lead to the provider giving the employer an updated activity prescription.

The primary obligation of the occ doc varies; it may be to the employer (Can this skyscraper worker be productive and safe?), to the public (Does this airline pilot create risk to the public?), or to the individual (Can this worker safely perform full duties without further risk to him or herself after this work-related injury?). Frequently, there is consensus among parties as to the outcomes of these determinations. For example, it is in the interest of both an injured worker and employer for the occupational medicine provider to give an activity status report that prevents further injury.

Fitness evaluations and determinations are not without controversy. Any time a health care provider comes between an individual and the work he or she wishes to perform, there is a potential for conflict. Workers who present for pre-employment fitness evaluations not surprisingly want the provider to medically approve them. Infrequently, there is a conflict between the provider’s and worker’s own assessment of the risk. Particularly when there is a conflict, it is important to make fitness determinations based on published guidelines or population studies with functional and safety outcomes, when available. Examples of such guidelines and reports include National Fire Protection Association guidelines for firefighters,iv ACOEM’s Law Enforcement Officers’ guidelines,v and medical review board or medical expert panel reports from the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Association.vi Some of the challenges faced in such determinations have been highlighted in the literature, as well.vii, viii

Surveillance

Surveillance helps ensure that the work and work environment do not hurt the individual, other workers, or the public. In some cases, specific monitoring activities are mandated by government bodies, such as OSHA. Common OSHA surveillance activities include regular audiometric exams to monitor the effects of noise at the workplace and periodic examinations for workers exposed to lead. Surveillance does not always prevent injury in the worker being monitored. It is generally a secondary prevention screening tool, meaning it does not prevent injury but helps detect it early—ideally before symptoms or irreversible damage develop. This allows for the employer to evaluate its industrial hygiene and safety program to prevent further injury to the worker or initial injury to coworkers or the public.

The components of these activities may vary from questionnaires to physical examinations to laboratory work and imaging studies, or any combination. Many examples of surveillance activities required in the United States are described in Medical Screening and Surveillance Requirements in OSHA Standards: A Guide, published by the U.S. Department of Labor.

Work-Related Injury Care and Causation Analysis

When the preventive measures noted above fail, or when other circumstances lead to injury or illness, it falls on the occupational medicine provider to care for the worker. Above all, we must ensure the patient gets proper care for any complaint. However, the ongoing care we provide is typically limited to work-related injury or illness. Therefore, a critical element of the patient evaluation is to establish the causation of the complaint. If it is not deemed work related according to the laws under which you practice, the individual should appropriately and speedily be transferred to the appropriate caregiver.

When the injury or illness is work-related, the occ doc can essentially become the primary care provider, coordinating treatment for that injury or illness until the individual has returned to the previous status or reached maximum medical improvement (MMI), or a state where it is unlikely that significant changes will occur in the near future. In some jurisdictions, and when necessary, the occupational medicine practitioner continues to follow the patient on a periodic basis even after the patient reaches MMI.

In addition, for complex work-related cases (which tend more frequently to be illnesses than injuries), the occ doc fills the role of consulting specialist. In these cases, the providers’ knowledge of causation, and the effects of work and the work environment, are essential. In these situations, occupational specialists bring expertise in areas that are not necessarily within the purview of primary care providers, such as exposure pathways, dosing, toxicology, and epidemiology, which can play important roles in these settings.

Conclusion

The better an occ doc understands the work activities and work environment of the population(s) being treated, the better and more precise the care and recommendations he or she can give. A great occ doc will be able to engage with the workers, management, industrial hygienists, and safety professionals as needed.

The occ doc provides a satisfying service to workers, employers, and the public through high-quality application of preventive and population health tools. For many, that satisfaction comes as we are able to apply those tools to individuals one at a time—maintaining the one-on-one touch so many of us sought in pursuing medicine as a career. At the same time, we continue to challenge ourselves by learning how to apply what we learn in each interaction to whole populations and frequently assisting employers in creating and applying policy to treat and prevent injury and illness among entire groups of workers.

- Gochfeld M. Chronologic History of Occupational Medicine. JOEM. 2005;47(2):96-114.

- Gochfeld M. Occupational Medicine Practice in the United States Since the Industrial Revolution. JOEM.

- 2005;47(2):115-131.

- Franco G, and Franco F. Bernardino Ramazzini: The Father of Occupational Medicine. Am J Public Health. 2001; 91(9): 1382.

- NFPA. NFPA 1582: Standard on Comprehensive Occupational Medical Program for Fire Departments (2018).

- Accessed at http://acoem.org/LEOGuidelines.aspx.

- More information at https://www.fmcsa.dot.gov/regulations/medical.

- Dale AM, et al. Post-Offer Pre-Placement Screening for Carpal Tunnel Syndrome in Newly Hired Manufacturing Workers. JOEM. 2016; 58(12):1212-1216.

- Pachman J. Evidence Base for Pre-Employment Medical Screening. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2009; 87(7):529-534.